Most of the time, upon receiving that rejection letter from your dream school or dream job, we concede and accept defeat for one of two reasons. The first is that we know that after throwing a little tantrum upon receiving that ‘no’, there will always be another job or school. But in the other scenario where we accept defeat, it’s usually because repeatedly applying to the same place on an endless loop diminishes us ever so slightly. Born almost entirely out of ego, this feeling can be overcome if you want it badly enough. As a younger journalist, I find myself on my second or third round of applications to certain news publications as I manage to collect these bylines as if to say ‘I’m better than I was before!’, which as I said already, does little to nothing for your sense of self-worth. But as far as job hunting goes in this economy, a little begging feels like a necessary sacrifice for what might just lead to financial stability. In doing so, we’re also craving the validation that comes from being accepted to somewhere you were previously rejected. It feels good to squeeze your way in somehow and belong to an exclusive club whose windows you can look out of and stare at dozens of former you’s.

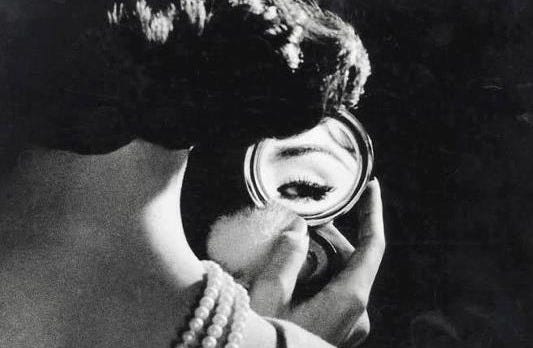

In the same way that certain institutions are able to create exclusive members’ clubs to wealth or success in this way, we can see where brands do the same exact thing, where instead of barring access to upward social mobility, they’re able to sell access to the illusion of upward social mobility, (therein lies the appeal). A lot of people don’t want to buy something that is seemingly available to everyone, and I’d wager that the desperation to be a part of the exclusive, is almost directly linked to how we feel about our own intrinsic value.

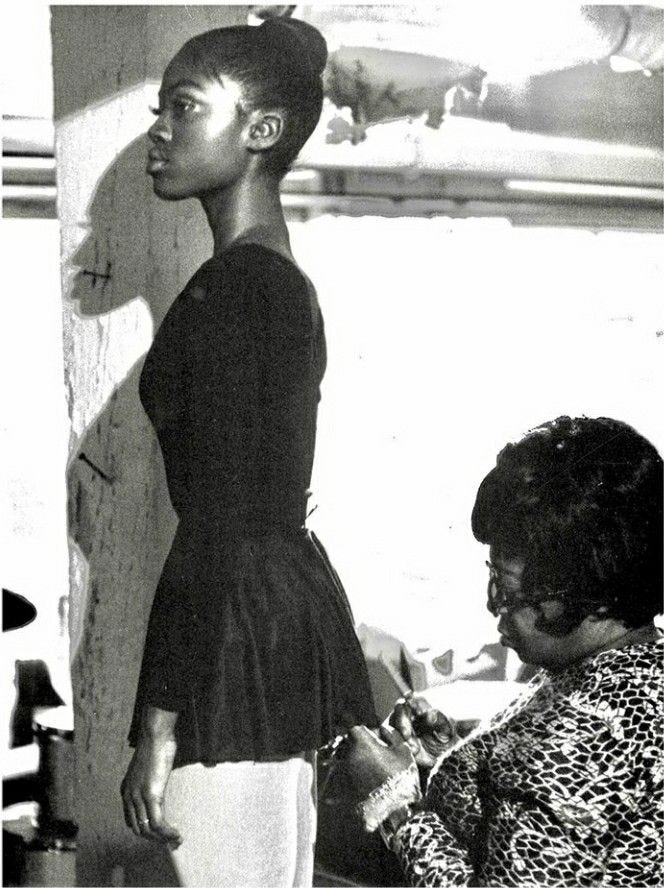

For black women, outside attempts to undermine our self-worth are nothing if not relentless. Even those beauty, wellness and lifestyle standards that seemingly change from one day to the next somehow remain consistent in their dedication to misogynoir. As such, we constantly find ourselves on the outside of whatever it is that’s trending now. In this way, we can hardly avoid feeling as if we’re in that same state of pleading - it’s almost unavoidable, save for the few black-owned makeup and fashion and skin or haircare brands. But for me, there are levels to this, and a point at which the tension between wanting to be accepted and realizing the emotional toll that process can take becomes too much. The name ‘Lululemon’ comes to mind, because I know that most of us are aware of the brands’ history with racism and yet, those workout tracksuit tops have almost become synonymous with images of ‘black luxury’ on Pinterest and TikTok and Ig reels.

For Those of You Who Don’t Know

Lululemon was founded in 1998 by Chip Wilson, a fitness enthusiast who discovered the benefits of yoga while seeking relief from back pain and sports injuries. Noticing a gap in the market for stylish yet functional activewear, he saw an opportunity to create yoga apparel that addressed common flaws like poor fit and lack of sweat proof fabrics. He’s since become well-known for designing a pair of lightweight, stretchy yoga pants using a blend of nylon and synthetic fabric, ensuring they allowed for a full range of motion. After consulting with yoga practitioners, Wilson launched Lululemon, and by 2000, the brand had its first standalone store in Vancouver. The name, however, as part of a supposed ‘marketing tactic’ to attract more attention in Japan, was chosen because its multiple "L"s would be challenging for Japanese speakers to pronounce…

“It's funny to watch them try and say it.”

& I could go on…

More recently he told an interviewer that he doesn’t know why black women wear Lululemon, as we’re not his target audience. It’s also worth noting that in 2012, Wilson also noted his clothing wasn’t for plus-sized women.

“They don’t work for some women’s bodies”.

Sounds a lot like another brand we know.

Brandy Melville, a brand we all love to hate, has since been criticised for their ‘one size fits all’ clothing, and their intentionally and exclusively all white, skinny female models and members of staff, so what’s the difference?

Brandy Melville illustrates the image of a blonde, Dutch, middle-upper-class woman, and their exclusivity goes beyond just clothing, they’re gifting you front-row seats to a club you’ll never gain access to, even after you purchase what it is actually on $ale. Lululemon spreads a similar message, but, is marketed as workout gear, clothing that people of all shapes, colours and classes would need in their every day, so the brand is far more appealing to a larger more diverse audience, and more of us can feel like we’re finally ‘on the inside’.

For black women, the obsession with Lululemon goes far beyond a desire to be apart of the latest trends. Given the overpriced nature of their clothing, Lululemon acts as a tool to signify wealth in the mainstream black female community, because workout jackets worth $100+ lie in that sweet spot, where they’re not completely out of the realms of affordability for the average gym goer, but are expensive enough to indicate you have some money to play around with. I for one am surprised that Tik-Tokers haven’t made an entire aesthetic out of these yet, but for now, I’ll be grateful that I haven’t seen clips on Fashiontok captioned ‘₊✩‧₊˚౨ৎ˚₊✩‧₊Lululemon girls’₊✩‧₊˚౨ৎ˚₊✩‧₊, showing aesthetic slides of Lululemon work out gear next to Stanley Cups and pastel pink or yellow coloured scrunchies.

Q: So why not get a dupe?

A: Because the emblem on the uniform is half the point,

(That should be obvious).

Our connection with the fashion and beauty industry as black women is that of a toxic relationship at the best of times and otherwise feels abusive. These industries and their representatives continue to implicitly or otherwise, let black women know that we are (once again excluded), and our programmed response is to do whatever it takes to earn their approval,

“If only we could just prove them wrong!”

That conversation that’s circulating online right now, about the ‘GHETTOFICATION’ of the brand as soon as it’s seen on black female bodies irritates me for a few reasons, the least of which is because the inference was made by a black girl, or for what this says about the way society views black women more generally. For me, my patience continues to thin every time I see another black girl claiming to subvert the stereotype by sporting a brand designed by a man who hates black women. It’s too ironic. For a group of women so committed to subverting the stereotype that assumes in us a kind of ‘cheapness’, we’re too easily bought in an effort to somehow transform the minds of those who never even considered including any of us.

The brand fits into that ‘quiet luxury’ side of wealth performance, that designs itself after exclusivity, but has somehow inspired this need to belong. When the Luxury Black Girl aesthetic initially made it’s way onto the digital landscape, I, amongst others noticed that the whole thing seemed to hinge on demonstrating that we too can exist somewhere in the picture of the almost exclusively white, ‘old money’ aesthetic.

Of course, pursuing identity through fashion is an old, accepted part of social behaviour.

So remind me, what exactly is the identity we’re trying to achieve here?

It would appear that some of us got tired of that ‘black female empowerment’ spiel that was circulating a couple of years back and had a kind of full circle moment all the way back around to the self-destructive indifference of decades past.

Such little time,

so much to prove.

Asisa

Sources:

https://sourcingjournal.com/topics/business-news/lululemon-founder-chip-wilson-certain-customers-plus-size-racist-japanese-486691/ SOURCING JOURNAL, Lululemon Founder Says Popular Brand Isn’t for ‘Certain Customers’

my biggest issue is that black women are the type of women to splurge on beauty / clothing products for more reason than one, and you … market against them? the hatred for us runs so deep and it’s so stupid to watch when people don’t understand that.

Such a lovely read 🫶🏽🫶🏽