I’m finding that now (online), queer culture is often represented by the discourse surrounding the identities it plays host to. When we aren’t combating the legislation responsible for infringing upon a number of civil liberties, we’re witness to the seemingly never ending battle between varying identities amongst sapphics or innumerable videos entitled “Warning signs: How to Detect DL men in 2025!”.

Where queerness remains stigmatised within the black community, the discourse is seemingly all that is highlighted. Across diaspora that despite knowing queerness in it’s history remains dedicated to ostracising it, specifically for the performance of an idolised blackness for those outside of the community, each and every conversation became about validation first and foremost.

After recognising the ways in which queerness has managed to survive, at times shrinking itself down, it’s worth examining what lies at the heart of queer culture as we understand it and often misunderstand it also. Specifically, for all the ways in which black queerness is so often appropriated in an effort to provide blood flow to a continuously dry and lifeless pop-cultural scene, understanding the origins of what have become mere accessories for most is all too crucial in 2025.

Having adopted its name from the annual ball Paris is Burning alongside the central ball mogul, Paris Dupree, the documentary (1990), directed by Jennie Livingston takes on the role of answering the question surrounding what lies at the heart of black queer culture. Having only watched the film a few days ago in honour of pride month, it felt like the perfect scaffolding to this conversation as a queer cult-classic now.

The House

As centres for trans and gay expression since the 1700’s, the ‘House’ is seen to embody kinship whilst illustrating where familial bonds extend far beyond blood ties.

In the documentary, mother of The House of Labeija, Pepper Labeija spoke about the ways in which the house offers respite from the unforgiving nature of a largely queer-phobic society, whose anti socialism is often exemplified within traditional family structures. After being ostracised from one's own, there exists a choice for the individual between solitude and relocation,

“When someone has rejection from their mother or their father they search for someone to fill that void (...) I know this from experience”.

Pepper Labeija

In the 90’s across NYC (the film's location), the youngest of the black queer folk seen adopted into new families were as young as thirteen, learning what it means to be black and queer before learning what it means to fully function in society as an adult. Teenagers often recanted experiences of neglect or abandonment from biological parents as a part of what had become known as the common queer experience. After the expectation of desertion is fulfilled by blood relatives bridled with hatred and ignorance, in came a unique and authentic level of acceptance from the house. Here is where a new kind of primary socialisation occurred, where mothers like Pepper would also commit themselves to the role of protector and teacher regarding other aspects of queer culture (those innate characteristics I’ll go on to elaborate upon).

The Ball

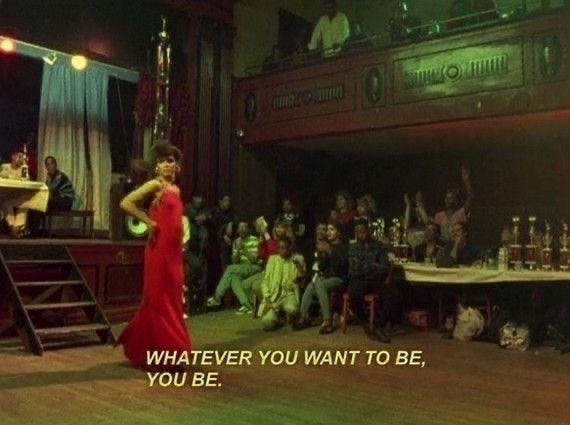

From inside the houses of Labeija, Ninja or Extravaganza, you might find yourself attending the ball, an aspect of queer culture that has continued to grow - nowadays finding its way into the calendars of even those who don’t identify as queer themselves. The culture found at balls specifically has provided a framework for what has become known as ‘Gen-Z slang’ - a bastardisation that might be explained by both appropriation alongside a theoretically more liberated and tolerant younger population of teenagers and young adults. Nevertheless, the iconography of the ball is better represented in its foundation as a runway to what constitutes fame within this subculture.

“The Ball is as close to fame as we’re ever going to get” stated just one of the voices narrating the documentary, after which an insight into the hours-long preparation process was shared, as the groundwork for the chance to carve out space amongst a crowd filled with eccentricity.

Having evolved throughout time, gradually becoming increasingly expansive, the categories of various balls continued to evolve much like beauty trends in the mainstream. Formerly, the most commonly seen looks came from drag queens emulating the LA Showgirl - the picture of decadence and extroversion. Following on, a more distinct ‘movie star’, Marilyn Monroe-esque figure emerged, to be succeeded by the more sultry tone of the 90’s, where many strived for the looks of famous supermodels of the time, (Iman for instance comes to mind).

As time went on, the categories became increasingly niche, representative of both the unique creativity and poignant ability to observe often found amongst marginalized communities. In the film, category titles ranged from ‘Town or Country’, to “Butch queen’s first time in drag at a ball”. As a common sub category in it’s own right, often attached to other categories, the concept of ‘Realness’ provided room for the queer population to experiment with so-called normativism, where one interviewee explained where the idea of realness as a means of looking as much as possible as ones straight counterpart was not a takeoff or satire, but was more so the practice of perfecting one's' illusion.

“When they’re undetectable, when they can walk out of that ballroom and into the sunlight and onto the subway and get home and still have all their clothes and no blood running off their bodies, those are the femme realness queens”.

To pair nicely with the descriptors allocated by designated categories, were fashion pieces that helped to narrate the story of the individual. Here there is an emphasis on acquisition over creation, where embodying fashion in the context of an underground hall pod fame became a way to temporarily transcend the barriers imposed by class and race, alongside norms surrounding gender and sexuality. To aid this mission, ‘Mopping’ was introduced, as a process involving meticulously scanning department stores for perfect items and quickly taking them, reducing the meaning of the price tag to nothing.

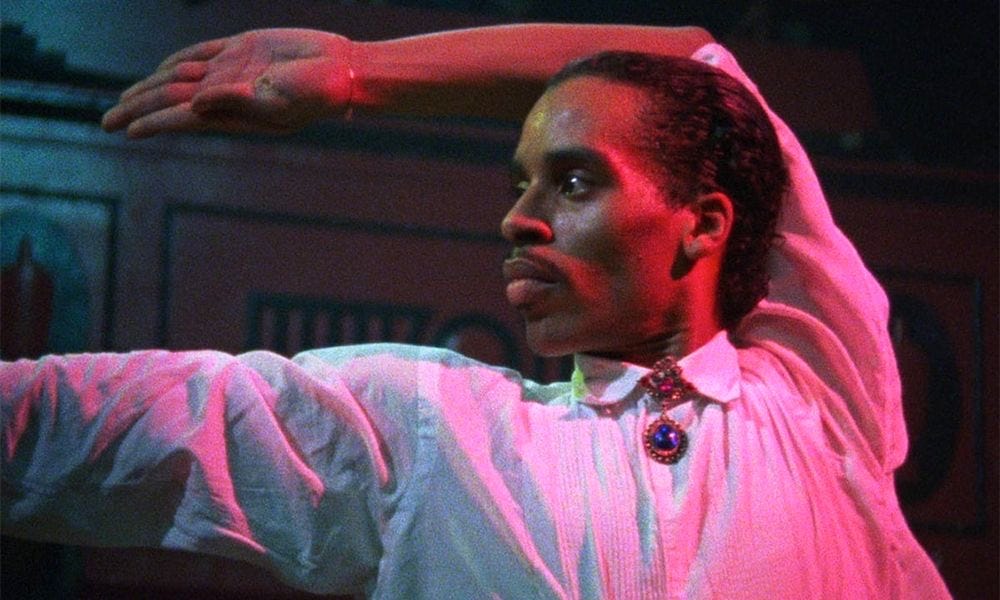

To complete the story, is the performance exhibited by the runway star. On this strip, voguing became par for the course, telling stories of glamour or transformation, often involving mime-like interpretation, combined with the unique flare of the individual, and polished off with sharpness and precision. Where brutality and violence became associated with powers outside of the community, voguing also became a way for those who didn’t like each other to express their opposition using their own unique language.

The Survival Tactics

It certainly feels as though it’s almost impossible to discuss the black queer experience without touching on survival or rather the means through which one might survive.

In the context of NYC in the 90’s for the black gay and trans population, questions about survival extended themselves far beyond concepts of passing or acceptance. Oftentimes, the idea of survival became predicated upon seemingly basic necessities like financial stability or healthcare. For Venus, one of the documentary’s most featured, it was an ongoing hardship to find the balance between seeking economic stability by whatever means necessary and ensuring personal safety, particularly against a violently transphobic and homophobic male population. The announcement of Venus’ own murder towards the end of the documentary, cemented the reality that the fear of being attacked or murdered is not in any way abstract, but is unfortunately embedded in queer life. As such, facets of queer culture like the houses and the balls hosted by them, helped to provide visibility within a uniquely safe space. This leaves us to question how queer culture at its core is often seen responding to violence rather than being defined by it, where a resilient yet equally sensitive population continues to find ways to adapt and survive around the ever-changing landscape of queer acceptance in society.

The title Paris is Burning signifies the simultaneously unrelenting and illuminating essence of queer culture - characteristics which some might say lie in its heart. Like the flame, the individuals seen to represent it are not so easily restrained - committing to self-determination whilst exhibiting an unparalleled beauty.

Asisa

Beautiful . Queer culture needs this type of unprejudiced representation.