The Bones of Heathcliff’s Character : Wuthering Heights (2026)

Mourning The Loss of Identity in Adaptation

I suppose the only issue with only ever seeing oneself at the centre are the few times when the spotlight shifts ever so slightly. It must be disconcerting, unfamiliar and cold to watch as the audience thirsts for a new perspective having grown increasingly tired of your own. In a discussion about cultural capital, it can be uncomfortable to confront the idea that literary classics - typically a subgenre reserved for the white, privileged establishment - occasionally feature Black or Brown characters, especially when these characters don't conform to expectations of palatability.

In response to this cultural shock, we might hope that the white, middle or upper class creative director might adjust their thinking - daring to share the focus with those to whom it’s so rarely afforded, particularly in times where the source material demands this. Instead, we’re forever forced to keep our expectations low, after being so frequently disappointed upon realising they’d sooner butcher the story than relinquish their position or overlook an opportunity for increased profit.

Aside from its ability to detail a captivating romantic tale, Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1846) serves as a critique of the rigid class structure of Victorian society. Central to this critique of course, is the creation of Heathcliff’s character, who acts as both a microscope onto the dehumanisation and marginalisation of non-white and/or poor individuals in this context, in addition to offering resistance against notions of an immutable class structure that governed the widespread understanding of power and wealth at the time. As Heathcliff, a poor orphan who is also indicated to be of mixed or Romani heritage manages to rise in spite of systemic exclusion, the story also explores class conflict whilst granting Heathcliff - an individual without privilege - some agency as he becomes vengeful, managing to destroy the lives of those who embodied his oppression.

Heathcliff’s relationship with Catherine, whilst vital to the story, is not solely responsible for the novel’s accumulated status as a literary classic. Primarily, their relationship serves as an avenue through which other themes, namely, the race/class divide demonstrated throughout the story can be intricately explored, particularly as their obsessive love and her devotion to him as an upper class young white woman opposes the hostility and hatred of those surrounding her, whilst creating a key conflict for the story.

Of course, everyone is welcome to their own interpretations, where those who find themselves unaffected by class-race discrimination in their daily lives might uncover more relatability to the characters by way of Heathcliff’s pain, or Cathy’s tragic innocence within the context of their love story. Romance novels or other forms of media are as popular as they are in light of their adaptability to anyone’s experience, where upon reading Wuthering Heights, the topic of discrimination may (for some) melt away as a desire to see oneself embodied in either main character takes over. For others like myself, the topic of discrimination remains the central tenant of the story, as it does a central consideration in my everyday life. Unfortunately, the target audience for many a corporation tends to take on the shape of the former, leaving the first film adaptation and many subsequent adaptations at great risk of butchering the original tale.

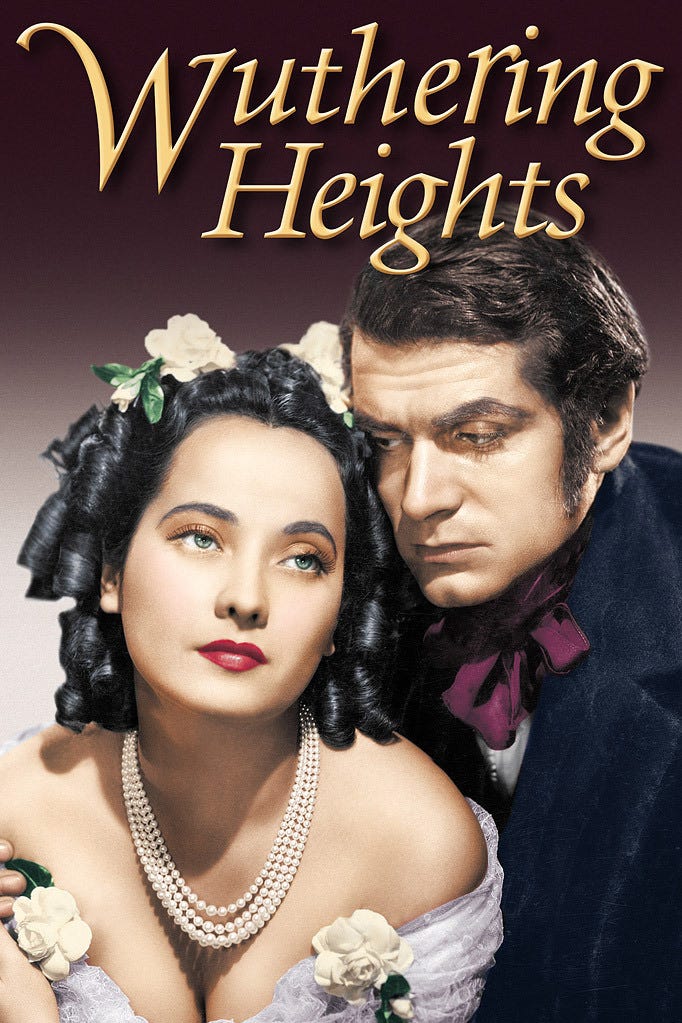

Notable film adaptations begin with Wyler’s 1939 depiction which is often commended for its expressionist style and rounding of the story’s… ‘edginess’. Perhaps it was in the process of ‘softening’ the film’s aesthetics that Heathcliff’s whitewashing took place, with Laurence Olivier (a white, English-French actor) having been cast as Heathcliff.

Similarly, a 1970’s iteration by Robert Fuest features Timothy Dalton, another white man as Heathcliff, with Anna Calder-Marshall playing the role of Catherine.

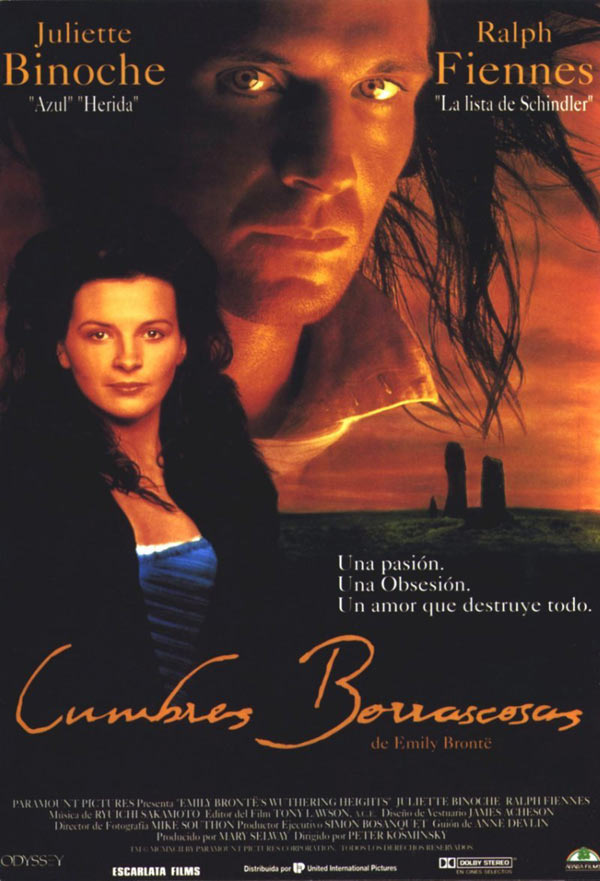

Peter Kosminsky’s 1992 edition starring Juliette Binoche and Ralph Fiennes features yet another white Heathcliff, despite being praised for portraying the ‘full story’ including the second generation story of the children of Cathy, Heathcliff and Hindley. This extension is what supposedly sets this version apart from other previous and future portrayals, though once again, it falls flat at executing the story as originally intended.

Finally, Andrea Arnold’s 2011 depiction helped to bring the story home with James Howson - a mixed race man playing a rarefied, darker-skinned Heathcliff alongside Kaya Scodelario as Cathy.

Over a decade later, Emerald Fennell’s casting choice for her adaptation of Wuthering Heights reverts us to that more familiar feeling of disappointment or dissatisfaction, as is the common experience for the average non-white film buff.

Despite Heathcliff’s long-debated ambiguous ethnicity - he is described in the novel as “dark-skinned”, highlighting Fennell’s decision to cast Jacob Elordi in the role for all the wrong reasons. To add insult to injury, actors of colour like British-Asian actor Shazad Latif and Vietnamese-American actress Hong Chau appear, occupying secondary parts, whilst offering us but a glimpse of what could have been. According to casting director Kharmel Cochrane, Wuthering Heights' existence as a work of fiction removes all constraints in regard to strict accuracy - an argument that once again ignores a major aspect of Heathcliff’s experience and subsequent motivations throughout his arc. Nevertheless, in her critique of the whitewashing of period dramas earlier this year for Vogue, Hannah Flint this raises the question of why the story must still default to white leads. The novel’s themes of love, obsession and social exclusion are universal, offering space for diverse representation even if in an event that the story itself didn’t already demand this. By contrast, she notes that projects like Bridgerton or Joel Coen’s Macbeth show how casting actors of colour in major period roles can resonate with global audiences.

The film is set to be released for Valentine’s Day on February the 13th, priming the film for guaranteed success in the box office, and ensuring that this adaptation is framed first and foremost as a romance film, erasing some of the story’s more complex and infinitely more compelling elements. In the contentious nature of today’s pop-cultural climate, an adaptation true to the source material would have served as a contrast to the litany of cheaper, opportunistic ventures that we have all been made to suffer. Instead, this adaptation starring Jacob Elordi as Heathcliff and Margot Robbie as Catherine accompanied by a soundtrack featuring Charli Xcx serves to proliferate the artificial, bare and surface level nature of far too many ‘blockbuster hits’ now.

Still, it feels as though the most frustrating aspect of this betrayal comes with the appropriation of a story of marginalisation in service of this distant and detached depiction. We know by now that the white filmmakers don’t take issue with reframing the pain of the marginalised as being somehow transcendent of identity and experience as to adapt our stories for their own, but I wonder what really remains of this body of work once its meat has been shed and only the bones remain, and how complex and layered Heathcliff’s character will appear once his experience of marginalisation is circumvented altogether. Heathcliff's struggle, his rage, his humanity - are all inextricably linked to his status as an outsider, as someone deemed less than, less worthy of the same care, dignity, and love afforded to those born into privilege. In Fennell’s hands, what we’re left with is not a confrontation with the injustices of society but a hollow, romanticized spectacle that misses the very pulse of Brontë’s story. To strip Heathcliff of his ethnic ambiguity, his class struggle and his marginalization, is to rob him of his power and his reason for vengeance. The inherent violence of his love, borne of a life spent outside the comfort of white, wealthy society, becomes merely a byproduct of his tortured heart.

In the end, to sever Heathcliff from his identity, is to sacrifice the very soul of Wuthering Heights as a story which challenges and critiques the oppressive structures of its time. The original story, whose essence will for now be lost to a polished commercialisation, will only survive by its legacy, (and through the complaints of an endless line of substackers intent on defending its honor).

Asisa

You make soooo many good points I love this piece