What Does Representation Mean to You?

With the outrage against Price's "Grounded in the Stars", it's certainly unclear.

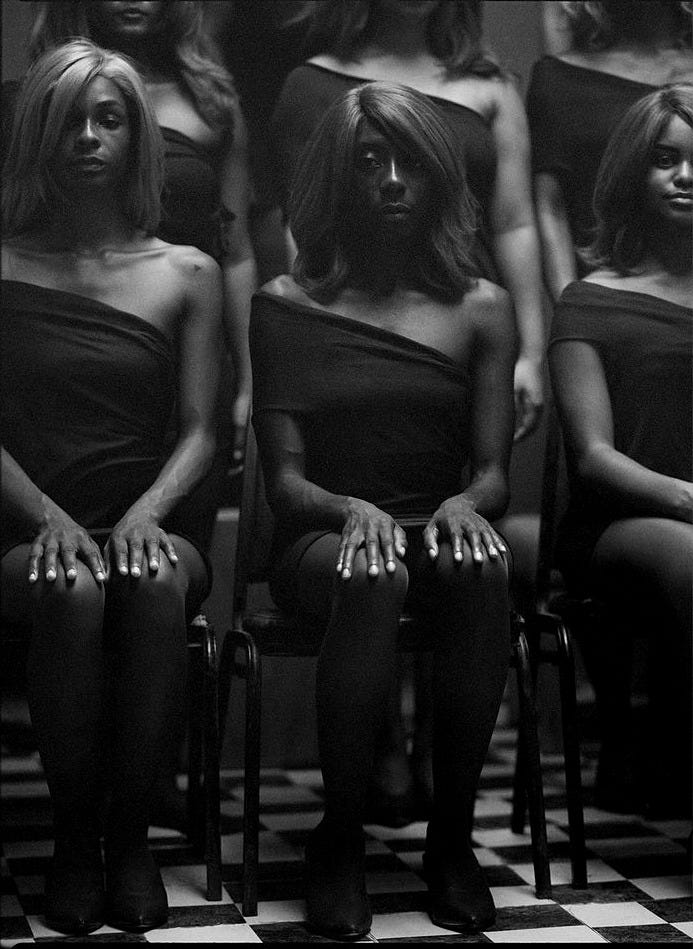

Between all the negative depictions of black women everywhere from reality tv to fictional stories, it’s easy to understand why the discussion surrounding misrepresentation is seemingly ongoing, particularly where we’re not so easily defined by tropes in television. As such, the representations thus far feel a little… flat, often portraying just a fraction of the black female experience or playing upon harmful stereotypes. So then, where there remains a multitude of portrays to be critiqued, the outrage surrounding Thomas J. Price’s sculpture “Grounded in the Stars”, is puzzling to say the least.

The 12-foot bronze sculpture, depicting a young Black woman in casual clothing is said to deliberately mirror Michelangelo’s David to challenge traditional heroic imagery and disrupt prevailing ideas about who deserves monumental representation.

The British artist claims to redefine triumph through the statue’s posture, clothing, and scale, inspiring thought as to who should be immortalized in public spaces. Officially, Price’s goal is to “Evoke deeper reflection on identity, the human condition, and cultural diversity”.

But who is she?

Reportedly her identity is not based on a single person; rather, she is an amalgamation constructed from photos, observations, and open calls spanning Los Angeles to London, aiming to emphasize universal representation over individual likeness. However, regardless of the artists’ good intentions, and the inspiration behind the piece, many were left unsatisfied with the aesthetics, claiming Price should have constructed a more flattering image.

Comprised of potentially hundreds of real faces, it’s fair to say the structure represents the average black woman across the diaspora, where ‘averageness’ isn’t necessarily a flaw in this context, but alternatively, works against what we know about the need for black exceptionalism where beauty standards for women are far from the exception.

Of course if this thin lens were spread out evenly, applying varying demographics to the same degree, this could be a more two dimensional conversation about how limiting beauty standards tend to be generally. But much to our disappointment, mediocrity is praised and even fetishished in other instances. Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa serves as evidence for this truth in a conversation about visual art, but we see this narrative play out on our screens all the time.

Girl Next Door!

“The girl next door”, often seen in romantic comedies featuring almost all-white casts is paraded in western media as being the sheer iteration of a mundane and effortless beauty. She isn’t considered particularly exceptional and yet inspires such devotion from her love interest in light of her organic texturedness. She is ‘down to earth’ and ‘relatable’ - the pure embodiment of being ‘pretty without knowing it’, where her humility underlines the entire appeal. Of course this archetype is just as steeped in misogyny as just about every other archetype claiming to accurately portray different kinds of women in film. But what interests me about this archetype specifically when paired against the outrage against the Times Square statue, our ‘girl’ (woman) next door, is how it epitomises ideas surrounding what it means to be white and exceptional versus our reality. Girl next door is perceived to be beautiful because she is white, whereas our woman next door might be considered beautiful in spite of her blackness provided she conformed to certain standards in the west. But as it happens she doesn’t, exposing her to scrutiny instead of praise…

Comments under influencer Anna Renn’s video read the following…

I suppose it must be said that internalisation is nothing new, and you’d be hard pressed to find any demographic of women whose minds aren’t impacted by westernised beauty standards. But for black women, as those who are often depicted as the antithesis of ‘pure’, white beauty, we’ve become intimately familiar with the practice. We already know the ways in which expectations have helped to dictate the ways we style our hair and treat our skin and our bodies, which for the most part I’ve come to accept in the name of allowing black women to live their lives without constant criticism. But for me, the condition here is that we’re at the very least, honest and conscious about our choices and the way these choices inform the stories we continue to tell ourselves and each other about what it means to be beautiful. By contrast, the outrage at the depiction of the black woman in Times Square reeks of dishonesty. “Why do they always have to make it weird, why couldn’t they have made her beautiful?”, Anna Renn questioned, without first questioning why she struggled to see beauty outside of such strict constraints.

By now the practice is as old as time, where after the transformation comes the performance. If we were a community living in isolation, performing blackness in such a particular fashion would hardly matter as diverse as we are. But in front of an audience, the representation of black womanhood must be near to perfect. I’m having a hard time believing that people are struggling to identify with our representation in Times Square, but find it far easier to believe that people don’t want to identify with her and more to the point, are trying their hardest to prove that they don’t. “She doesn’t represent me!”, feels kind of synonymous with “Pick me, choose me!”, without having to outline exactly why, (see fatphobia, colourism, featurism, texturism and other just as debilitating ‘isms for the specifics).

Alternatively, contrasting opinions on this statue highlight the many (considerably larger and more noticeable) images of Beyonce propped up on screens all around the famous location. As exceptionally successful and talented as she is, in addition to benefiting from certain privileges according to the prejudices just mentioned, you’d likely never hear complaints from the masses surrounding her supposed embodiment of black women everywhere. Contrastingly however, this one, smaller, far less noticeable portrayal has provoked an entirely different reaction.

What’s more is the widespread rejection of the statue helps to merely amplify voices coming out of the MAGA camp as if they weren’t loud enough on their own. According to an article by The Root’s Angela Wilson,

“Comments from MAGA included comparisons to Lizzo, their “confusion” that the statue was made in the image of a gorilla, and even calling the statue “Tyquisha” who “looks horrendous. (...) The racist and downright sad remarks continued on X: “And it will be taken down once she goes to prison,” “That statue wants to know what gratuity means,” and “You cannot convince me that’s not Fat Albert.”

To compliment their sentiments - these direct and explicit iterations of racism, came voices emerging out of the black community to help verify them, and as long as we’re considering impact, the truth remains, that hatred is hatred nonetheless.

Takeaway

If only the heat of the criticism would melt the statue so that you could scrub her from your mind. Instead, accepting that it won’t and she’s here to stay is certainly simpler. At the same time, where statues are after all, representative, her constancy can be used to represent our immutability despite the tireless attempts of erasure from those within the community and those just looking in.

Mostly the outrage surrounding “Grounded in the Stars” exemplifies the need for it. Though there’s nothing wrong with her physically, Price’s intentions weren’t to showcase black beauty at all. The emphasis on what people are considering his failing in this department speaks more to insecurity than anything else, and once again we can see how the statue is the perfect representation of black women everywhere. The conditions through which she is accepted mirror that of our own, where the hope is, she might carve off little pieces of herself for their eyes.

That being said, I for one, think the statue is just right.

Asisa

I’ve been frothing for someone to write about this and you hit the nail on the head. Maybe for once, the representation is for us and not to prove time and time again that we can be ‘attractive’ to white people.

Yesss, this! People’s reactions definitely speak to an obsession with exceptionalism. I’d also be curious to know why they’d think a statue modeled after some “baddie” archetype would be more relatable? Few people look like that either. It’s definitely projecting insecurities/other internalized shit onto it!